|

Abstract: Two mollusk collections, roughly spanning the 30-year existence of

the Crosby Sanctuary, are reported.

Selected zoogeographic,

archaeological, historic, nomenclatorial, and taxonomic aspects of this

fauna, numbering 30 species, are discussed relevant to three large aquatic

gastropods, Viviparus georgianus, V. intertextus, and Pomacea

paludosa.

The

Duval Audubon Society (DAS) administers a tract of 408 acres of

predominantly bottomland hardwood swamp donated by J. Ellis and Addie Weltch

Crosby in the early 1980's (Crosby

Sanctuary). This land is a segment of a

major wildlife habitat corridor between the Ortega River (McGirts Creek), on

which I live, and Black Creek, in Duval and Clay Counties respectively.

On June 22, 1980, during the lengthy process of land-transfer, I accompanied Lenore McCullagh, who served as DAS liaison with the Crosbys, and her husband, Henry,

my partner in medical practice, on a riverine reconnaissance of the property

with a focus on its malacofauna. After parking on the west side of Blanding

Blvd. near the Duval-Clay boundary, we launched our canoe from the

right bank of McGirts and paddled upstream about an half-mile. Almost

immediately we reached the NE corner of the tract and traced its northern

boundary on our left while we proceeded roughly westward. Progress was leisurely

as we sampled the sandy bottom and submerged vegetation in the tannin-stained

but clear waters. Girding the serpiginous watercourse through much of this

stretch is paralotic swampland. Here we occasionally put ashore in the cool

shade and prospected for land snails on habitable patches within the hydric

hammock, in which Bald-cypress, Red Maple, Sweetgum, and Tupelo were the

dominant cover.

It was a pleasant excursion. Furthermore, the

periodically-edited species account in my field log indicates 22 species, all

but four aquatic, were collected at this (extended) station. That's a healthy chunk of

biodiversity - maybe not by ornithological standards, but reasonably robust by NE

Florida molluscan measure; see Highlights among Northeast

Florida non-marine mollusk survey locations.

These

taxa are among those tabulated in the appendix below.

In May of this year, Jacksonville Shell Club (JSC) member and scientific author,

Heather McCarthy (McCarthy and Lisenby, 2010), asked me about the status of a NE

Florida aquatic snail, Amnicola rhombostoma (F. Thompson, 1968) the

Squaremouth Amnicola, described from Peters Creek in Clay Co. and historically

known from less than a dozen places in Clay, Putnam and St. Johns Cos. Heather

could find no evidence the species had been collected since 1981. Since I had

reason to believe it might be living in McGirts Creek, Heather called a meeting

at the newly-opened Marine Science Research Institute of Jacksonville University (site of the October

27 JSC meeting). On September 13 I met Heather and two St. Johns Riverkeeper

professionals, Jimmie Orth and Kelly Savage, in Jimmie's office. We ultimately

decided to join forces with DAS President Pete Johnson, who kindly allowed

Heather, Kelly, and me entry through the south gate of the Crosby at 427

Aquarius Concourse in a quiet NW Orange Park neighborhood three weeks later.

Pete also served as our guide for about three hours as we trekked through parts

of the sanctuary. The initial segment of the walk was through disturbed,

mostly-cleared high ground. Shortly, we entered the bottomland swamp and later

emerged at the power-line sward less than a half mile to the north. This area is

a very boggy grassland maintained by the power company. We then slogged

approximately eastward in the sward and encountered what appeared to be a

southern tributary of McGirts Creek.

Although we failed to find the Squaremouth Amnicola, we did encounter lots of

aquatic snails along the trek, and they, along with a brace of clams and eight

land snails yielded a total count of 16 species for the portion of the tract we

managed to cover. All are included in the appendix below and bring the

cumulative Crosby Sanctuary mollusk species inventory to 30 species. The three

largest aquatic snails have particular resonance with the Crosby Sanctuary, the

St. Johns River, and in the history of science. Each is discussed below.

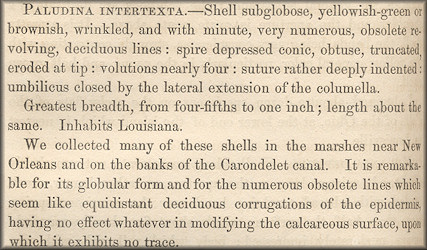

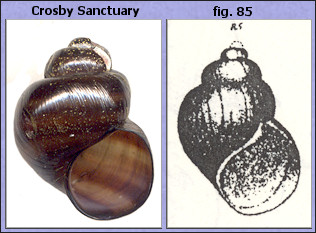

Viviparus georgianus

(I. Lea, 1834), the Banded Mysterysnail, has the distinction of being one of the

29 species described in the first scientific conchological publication by an

American author (Say, 1817). Although he suspected it was somewhat different,

Thomas Say (1787-1834) nonetheless identified his material as Lymnaea

vivipara and referred to Helix vivipara Linnaeus (1758: 772-773;

species 603) as presented by the Englishman William Donovan (1801: plate 87).

This latter taxon is now recognized as exclusively Old World in distribution.

Seventeen years later, a fellow Philadelphia Quaker, Isaac Lea (1792-1886),

recognized this, described it as new to science, and gave it a new name,

Paludina georgiana. This cognomen, after generic reassignment, is how we

know this

snail today, yet its relevant taxonomic history dates to the dawn of binominal

nomenclature and even earlier (see Linnaeus, 1758). A Crosby specimen is here

juxtaposed with Lea's type figure. The type locality is not far from here: "Hopeton, near

Darien, Georgia" (Lea, 1834: 116: pl. 19, fig. 85). Many other non-marine mollusks were

originally collected in or very near Hopeton, the plantation of James Hamilton

Couper, a renaissance man who played a prominent role in the elucidation of the

malacofauna of the Old South (Lee, 1978: 4-5). Taxa like

Littoridinops tenuipes (Couper, 1844), Triodopsis hopetonensis, and

Anodonta couperiana commemorate his industry. Viviparus georgianus

(I. Lea, 1834), the Banded Mysterysnail, has the distinction of being one of the

29 species described in the first scientific conchological publication by an

American author (Say, 1817). Although he suspected it was somewhat different,

Thomas Say (1787-1834) nonetheless identified his material as Lymnaea

vivipara and referred to Helix vivipara Linnaeus (1758: 772-773;

species 603) as presented by the Englishman William Donovan (1801: plate 87).

This latter taxon is now recognized as exclusively Old World in distribution.

Seventeen years later, a fellow Philadelphia Quaker, Isaac Lea (1792-1886),

recognized this, described it as new to science, and gave it a new name,

Paludina georgiana. This cognomen, after generic reassignment, is how we

know this

snail today, yet its relevant taxonomic history dates to the dawn of binominal

nomenclature and even earlier (see Linnaeus, 1758). A Crosby specimen is here

juxtaposed with Lea's type figure. The type locality is not far from here: "Hopeton, near

Darien, Georgia" (Lea, 1834: 116: pl. 19, fig. 85). Many other non-marine mollusks were

originally collected in or very near Hopeton, the plantation of James Hamilton

Couper, a renaissance man who played a prominent role in the elucidation of the

malacofauna of the Old South (Lee, 1978: 4-5). Taxa like

Littoridinops tenuipes (Couper, 1844), Triodopsis hopetonensis, and

Anodonta couperiana commemorate his industry.

The Banded Mysterysnail has a very wide distribution in eastern North America

(Clench, 1962), and it is particularly abundant and ubiquitous in the St. Johns

River system, where their empty shells are the principal component of discrete,

massive shell mounds on the flanks of the main river. Harvard Professor and

Peabody Museum Director, Jeffries Wyman (1814-1874), arguably the original archaeomalacologist, meticulously studied all eighteen of these mounds along our

river, a destination in part forced on him by poor health. His sentinel work

(Wyman, 1875) had not quite come to press when he died suddenly, but friends saw

to its posthumous publication. Although these extensive mounds' raison d'être

had been a mystery for many years, by placing the billions of Viviparus

shells in context with archaeological evidence of human activity, he proved that

they were in fact kitchen middens and reflected centuries of Native American

habitation and resource exploitation.

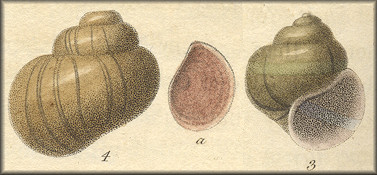

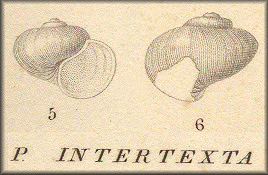

To my initial bafflement, two living adult Viviparus

intertextus (Say, 1829a: 244), each about an inch in height, were found by

blindly netting the swampwater substrate at a culvert under the earthen causeway

which was our northward pathway (see image at top of page). The point was about half the 0.4 mi distance from the gate to

the power line swath. The Rotund Mysterysnail is predominantly an inhabitant of

the Ohio-Mississippi and Mobile River Systems (Clench and Fuller, 1965), and its

presence in Florida had previously only been hypothetical (Thompson, 1984: 17;

2004) and then possibly only in the panhandle (Thompson,

2004: species

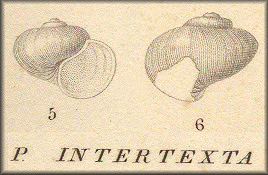

13b). Say's description of Paludina intertexta was reprinted in

Binney (1858: 146) and is reproduced below.

While there was no type figure, the

author redescribed and figured this species in his magnum opus, American

Conchology, two years later (Say, 1831: pl. 30, fig 3, 3a).

Those figures, depicting two different shells, are here juxtaposed with images

of one of the Crosby specimens. |

|

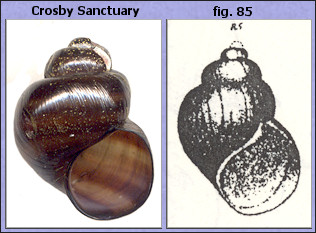

A few days later, I dissected the two specimens and found about a dozen

juveniles in the "uterus" of each. The very friable, flat-topped shells of these

"embryos" varied in size from 2 to 3 mm and had a very different appearance from

the

adult

shells from which they were taken

and from unborn of V. georgianus. They are perfectly

represented in an engraving taken from Haldeman (1871: pl. 10, figs. 5, 6).

Besides yielding some insight into the allometric growth of this species and the

fundamental morphological differences between it and V. georgianus, this

discovery unequivocally documents reproduction in this novel, isolated

population. In their own small way, these Rotund Mysterysnails and their story

emphasize the value of aquatic preserves and lend the Crosby Sanctuary a little

more credence as a refuge in this world of rampant growth and habitat

destruction.

A few days later, I dissected the two specimens and found about a dozen

juveniles in the "uterus" of each. The very friable, flat-topped shells of these

"embryos" varied in size from 2 to 3 mm and had a very different appearance from

the

adult

shells from which they were taken

and from unborn of V. georgianus. They are perfectly

represented in an engraving taken from Haldeman (1871: pl. 10, figs. 5, 6).

Besides yielding some insight into the allometric growth of this species and the

fundamental morphological differences between it and V. georgianus, this

discovery unequivocally documents reproduction in this novel, isolated

population. In their own small way, these Rotund Mysterysnails and their story

emphasize the value of aquatic preserves and lend the Crosby Sanctuary a little

more credence as a refuge in this world of rampant growth and habitat

destruction.

Pomacea paludosa (Say, 1829) is aptly dubbed the

Florida Applesnail as it is endemic to our state. Like the Banded Mysterysnail,

when it was originally reported in the scientific literature, the name applied

to it required correction. In this instance, it was not a misidentification but a

nomenclatorial gaffe that accounted for the problem. Initially the name Ampullaria

depressa Say, 1824 was introduced for snails collected by Say in 1818 at

"Mr. Fatio's Plantation" (Say, 1824: 12, 13; plate 14, fig. 3) and by John

Eatton LeConte (1784 – 1860), who conducted an official expedition to discover

the source of the St. Johns River under the auspices of Secretary of War John C.

Calhoun in 1822 (Lee, 1978: 6-7). This LeConte, like his brother, son and

nephews of the same surname, was a renaissance

naturalist

in the style of their Georgia low country neighbor, James Hamilton Couper (Lee,

1978: 4-7). Beside bringing to light several mollusks, J. E. LeConte discovered

new herps, mammals, insects, and plants during his peregrinations in the

American Southeast in the service of the US Army Corps of Engineers.

It seems quite likely a son of Francis Philip Fatio

(1724-1811), a Swiss immigrant turned Florida planter (Historical

marker)

on the St.

Johns River in New Switzerland, St. Johns Co., was

host to Thomas Say and his party in early 1818 (see Lee, 2007 and

Daedalochila auriculata (Say, 1818) Ocala Liptooth).

The elder

Fatio had welcomed William Bartram, Say's great uncle, 44 years earlier

<

http://www.unf.edu/floridahistoryonline/Plantations/plantations/New_Switzerland.htm

>.

Beside the first

scientifically-collected Florida Applesnail, Say found the type material of the

Florida endemic landsnail, Polygyra [now

Daedalochila] avara, in the "orange groves of Mr. Fatio"

(Say, 1818: 276) during the visit.

As

mentioned above, Thomas Say's original name for this applesnail, Ampullaria

depressa is not legit. From the early days of binominal nomenclature, and as

now codified in the provisions of the "Code" (ICZN, 1999: Article 52), the name

A. depressa Say was unavailable for purposes of taxonomic nomenclature

because it is a primary junior homonym of A. depressa Lamarck, 1804 [a

Middle Eocene marine moonsnail-like fossil and type of the genus Ampullina

Bowdich, 1822 (now Campaniloidea: Ampullinidae)]. Five years later, after Say

had rusticated himself in New Harmony, Indiana, he indicated the nomenclatorial

predicament and replaced his Ampullaria depressa with A. paludosa

(Say, 1829b: 260; Say, 1840: 22). It is by this time-honored cognomen, after

generic reassignment, that the Florida Applesnail has been known since. A fine

rendition of a living specimen is figured here: Pomacea

paludosa hand colored plate.

Thus, through just the small lens of malacology, the history of geographic

and biological exploration has weaved a fine fabric, one which envelops

Riverkeepers, ecologists, conservationists, and other votaries of the natural

environment. The vision of the Crosbys and the DAS, who have endowed posterity

with the framework to appreciate this rich heritage, should be applauded.

Acknowledgements: The author expresses his gratitude to the DAS and Pete

Johnson for the opportunity to conduct this study and for the provision of the

habitat photograph used in this report, to Heather McCarthy for the germination

of the project, and to these two individuals and Kelly Savage for excellent

leadership and assistance in the field. William Frank is thanked for

professional editing of the images and formatting the text and Richard I.

Johnson for sharing his copy of the "holy grail" of American malacology, Thomas

Say's first conchological work (Say, 1817).

APPENDIX:

Mollusca of

the DAS Crosby Sanctuary, Orange Park, Clay Co., Florida

Phylogenetic order and linked to figure(s), not necessarily Crosby Sanctuary

specimens: 1980 = A; 2010 = B

Aquatic species

Elliptio ahenea (I. Lea, 1847)

Southern Lance A

Elliptio jayensis (I. Lea, 1838)

Florida Spike A

Elliptio occulta (I. lea, 1834)

Hidden Spike A B

Taxolasma paulum (I. Lea, 1840) Iridescent Lilliput A

Uniomerus carolinianus (Bosc, 1801)

Florida Pondhorn A

Eupera cubensis (Prime, 1865) Mottled Fingernailclam A

Pisidium punctiferum (Guppy, 1867) Striate Peaclam A

(non native species)

Sphaerium occidentale (Lewis, 1856) Herrington Peaclam A B

Campeloma floridense (Call, 1886)

Purple-throat Campeloma A

Viviparus georgianus (I. Lea, 1834)

Banded Mysterysnail A B

Viviparus intertextus (Say,

1829) Rotund Mysterysnail B

Pomacea paludosa (Say, 1829) Florida

Applesnail A B

Amnicola dalli johnsoni (Pilsbry,

1899) North Peninsula Amnicola A

Aphaostracon rhadinum

F.

Thompson, 1968 Slough Hydrobe A

Floridobia fraterna (F.

Thompson, 1968) Creek Siltsnail A

Pseudosuccinea columella (Say, 1817)

Mimic Lymnaea A

Physella heterostropha (Say, 1817)

Pewter Physa A B

Planorbella duryi (Wetherby, 1879)

Seminole Rams-horn A B

Laevapex fuscus (C.B. Adams, 1841) Dusky Ancylus A

Terrestrial species

Gastrocopta tappaniana

(C.B. Adams, 1841) White Snaggletooth B

Pupisoma dioscoricola

(C.B. Adams, 1845) Yam Babybody B

Oxyloma effusum (L. Pfeiffer, 1853) Coastal Plain

Ambersnail A

Punctum minutissimum

(I. Lea, 1841) Small Spot A B

Euconulus trochulus

(Reinhart, 1883) Silk Hive A B

Glyphyalinia umbilicata

(Singley in Cockerell, 1893) Texas Glyph B

Hawaiia minuscula (A. Binney,

1841) Minute Gem B

Ventridens demissus

(A. Binney, 1843) Perforate Dome B

Euglandina rosea (Férussac,

1821) Rosy Wolfsnail A

Mesodon thyroidus (Say, 1817) White-lip

Globe B

Polygyra cereolus

(Mühlfeld, 1816) Southern Flatcoil B

Binney, W. G. 1858. The complete writings of Thomas Say on the conchology of the

United States. H. Bailliere Co., New York. vi + 1-252 + 75 plates.

Clench, W. J., 1962. A catalogue of the Viviparidae of North America with notes

on the distribution of Viviparus georgianus Lea. Occ. Pap. Mollusks 2:261-287.

Clench, W. J. and S. L. H. Fuller, 1965. The genus Viviparus (Viviparidae)

in North America. Occ. Pap. Mollusks 2(32):261-287. July 9.

Donovan, E. 1801. The Natural History of British Shells, including figures

and descriptions of all the species hitherto discovered in Great Britain,

systemically arranged in the Linnean manner, with scientific and general

observations on each. Natural History of British Shells 3. Author and F. and

C. Rivington: London. [i], pls. 73-90.

Haldeman, S. S., "1842-1845" [1840-1871]. A monograph of the freshwater

univalve Mollusca of the United States: including notices of species in other

parts of North America. J. Robson, Philadelphia. 231 pp. + 40 pls. (colored

with duplicate B&W). [No. 1, 1840. Paludina. pp. 1-16, pls. 1-5, Suppl.

to No. 1, 1840. pp. 1-3; No. 2, 1841. Paludina. pp. 17-32, pls. 6-10; No.

3, 1841. Limnea. pp. 1-16, pls. 1-5; No. 4, 1842. Limnea. pp.

17-32, pls. 6-10; No. 5, 1842. Limnea. pp. 33-55, pls. 11-15; No. 6, 1842

[1843]. Physadae. pp. 1-40, pls. 1-5; No. 7, 1844. Planorbis. pp. 1-32,

pls. 1-4, Ancylids. pp. 1-14, pl. 1, index to Physadae, 2 pp.; No. 8,

1845. Amnicola. pp. 1-24, pl. 1, Ampullaria. pp 1-11, pls. 1-2,

Valvata. pp 1-11, pl. 1; No. 9, 1871. Paludina. pp. 33-36, pl. 11,

index to Turbidae, corrections, contents, pp. 41-43].

ICZN (International Commission for Zoological Nomenclature), 1999.

International Code of zoological nomenclature fourth edition. International

Trust for Zoological Nomenclature, London. pp. 1-306 + i-xxix.

<

http://www.nhm.ac.uk/hosted-sites/iczn/code/index.jsp

>

Lea, I., 1834. Observations on the naiades; and the descriptions of new species

of that and other families. Last part. Transactions of the American

Philosophical Society 5: 114-117. pl. 19, figs. 81-86. Read 18 April.

Lee, H. G., 1978. Nineteenth Century malacologists of the American South.

Bulletin of the American Malacological Union, Inc., 1977: 4-8.

Lee, H. G., 2007. The Ocala Liptooth reprised after ninescore years.

Shell-O-Gram 48(5): 1, 3-4. September. See also

Daedalochila auriculata (Say, 1818) Ocala Liptooth.

Linnaeus, C, 1758. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes,

ordines, genera, species cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis.

Tomus I. Editio duodecima, reformata. Laurentius Salvius, Holmia

(Stockholm). Pp. 1-823 + i. [Reprinted in facsimile by the British Museum of

Natural History, London, 1956 (+ v).]

<

http://gdz.sub.uni-goettingen.de/no_cache/dms/load/img/?IDDOC=265100 >

McCarthy, H. P. and L. M. Lisenby, 2010. Sandhills, swamps, & sea islands

Environmental guidebook to northeast Florida. University of North Florida

Environmental Center, Jacksonville. x + 1-276. August.

Say,

T., 1817. Conchology. In Nicholson, W. [The

first] American Edition of the British Encyclopedia or Dictionary of Arts and

Sciences Comprising an accurate and popular view of the present state of Human

Knowledge volume 2 (of 6). A. Mitchell and H. Ames, Philadelphia. [1-14] +

plates 1-4.

Say, T., 1818. Account of two new genera, and several new species, of fresh

water and land shells. Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of

Philadelphia 1(2): 276-284.

Say, T., 1824. Appendix Section I. Zoology pp. 1-104 [mollusks 5-13 + plates

14-15] in Narrative of an expedition to the source of St. Peter's River,

etc., under the command of Major Stephen H. Long. Long's Expedition 2.

Philadelphia. vi+ 1-248 + 1-156. <

http://books.google.com/books?id=3YkUAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Long #>

[see "pp." 252 and (second iteration) 12, 13].

Say, T., 1829a. Descriptions of some new terrestrial and fluviatile shells of

North America [second installment]. The New Harmony disseminator of useful

knowledge 2: 243-258. Aug. 12. Not seen, but reprinted in Say, 1840 [q.v]

and available on-line at <

http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/33429#24> [see pp. 20-21] and see

Binney (1858: 146).

Say, T., 1829b. Descriptions of some new terrestrial and fluviatile shells of

North America [third installment]. The New Harmony disseminator of useful

knowledge 2: 259-265. Aug. 26. Not seen, but reprinted in Say, 1840 [q.v]

and on-line at <

http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/33429#24> [see pp. 22] and see

Binney (1858: 147).

Say, T., "1830" [1831]. American Conchology, or descriptions of the shells of

North America. Illustrated by colored figures from original drawings executed

from nature 3. Thomas Say, New Harmony, Indiana. [40 pp., unpaginated] +

pls. 21-30. Sept.; Sept.

Say, T. [ed. L. Say], 1840, Descriptions of some terrestrial and fluviatile

shells of North America. 1829, 1830, 1831. Lucy Say, New Harmony, IN. Title page

+ [i] + [5]-26. After March. <

http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/33429#24>.

Thompson, F. G., 1984. The freshwater snails of Florida A manual for

identification. University of Florida Press, Gainesville. x + 1-24.

Thompson, F. G., 2004. The freshwater snails of Florida A manual for

identification. Florida Museum of Natural History, Gainesville. <

http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/natsci/malacology/fl-snail/snails1.htm>; last

edited 6 March.

Wyman,

J., 1875. Fresh-water shell mounds of the St. John's River, Florida.

Memoirs of the Peabody Academy of Science 1(4): 3-94. |